Non-communicable chronic diseases (NCDs) are long-lasting health conditions that are not caused by infections and do not spread from person to person. Unlike acute illnesses, which often appear suddenly and resolve within days or weeks, NCDs develop slowly over time – frequently without obvious symptoms in their early stages. They can quietly progress for years before becoming clinically apparent, which is why they are sometimes referred to as “silent” diseases.

NCDs are influenced by a combination of diet, lifestyle, environmental, behavioral, genetic, and metabolic factors. Poor nutrition, physical inactivity, tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption, and chronic stress are among the common contributors. Over time, these factors can cause damage at the cellular and systemic levels – leading to inflammation, insulin resistance, high blood pressure, abnormal lipid levels, or other imbalances that gradually impair organ function and increase disease risk.

Because many NCDs evolve slowly, early warning signs are often overlooked or attributed to aging or lifestyle stress. For example, high blood pressure may not cause noticeable symptoms until it leads to a stroke or heart attack. Similarly, insulin resistance can exist for years before a person is diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. By the time symptoms appear, significant internal damage may have already occurred—making early detection, screening, and prevention efforts critically important.

In the United States, NCDs account for the majority of healthcare spending and chronic disease burden affecting nearly 50% of the population. In the last 20 years, the prevalence has increased by 7–8 million every five years. Today, an estimated 133 million Americans live with at least one chronic condition – 15 million more than a decade ago – with projections reaching 170 million by 2030. Conditions like heart disease, cancer, and diabetes continue to place escalating demands on families, employers, and health systems, accounting for over 85% of total healthcare expenditures. [American Hospital Association]

Despite their devastating impact, many NCDs are preventable – or manageable – when identified early. Smarter screening, smarter diagnostic testing, targeted therapeutic nutrition, physical activity, stress reduction, a healthy microbiome, and reduced exposure to harmful environmental factors can dramatically lower risk. Public health strategies focused on early detection and prevention are critical to reversing this trend.

Inflammation is the body’s natural defense response to injury or infection. In acute cases – such as a cut or viral illness – this response is short-term and essential for healing.

However, chronic inflammation is different. It is a prolonged, dysregulated immune response that can persist for months or even years when the underlying cause is not resolved. Unlike acute inflammation, chronic inflammation is not beneficial and can be harmful over time.

If left unaddressed, chronic inflammation can become systemic, contributing to cellular damage and dysfunction across multiple organ systems. It is a recognized as an early driver of many chronic diseases, including heart disease, diabetes, autoimmune conditions, and certain cancers.

Often called “silent, or hidden, inflammation,” as it may occur without obvious symptoms or may present subtly through vague symptoms such as bloating, digestive issues, joint pain, skin problems, fatigue, brain fog, anxiety, or depression.

Early identification and lifestyle-based interventions are key to reducing inflammation and protecting long-term health.

There is substantial evidence supporting the role of diet, lifestyle, and environmental factors in the development of chronic disease. Additionally, research has shown that prolonged dysbiosis and leaky gut can increase the risk of chronic disease.

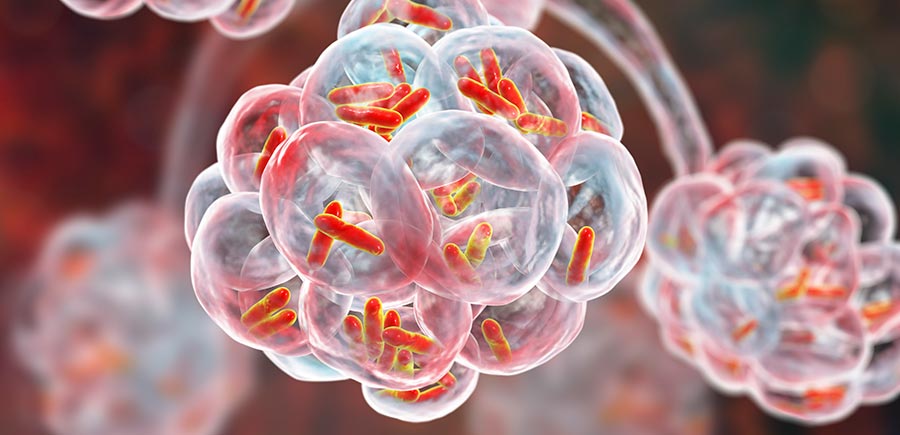

Dysbiosis is a clinical condition in which the balance of microorganisms within the gut—such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microbes—becomes disrupted. It can be disrupted by a number of factors such as poor diet, medications, sedentary lifestyle, overuse of antibiotics, stress, and environmental toxins.

Dysbiosis is characterized by a reduction in microbial diversity, an imbalance between commensal (beneficial) and pathogenic (harmful) microorganisms, as well as alterations in microbial metabolic activity.

The ‘harmful’ microorganisms can produce toxic byproducts (metabolites) that damage the cellular lining of the gastrointestinal tract. The gut lining can become inflamed and irritated. Over time, this inflammatory process can increase intestinal permeability and lead to what is commonly referred to as “leaky gut.”

“Leaky gut” occurs when the tight junctions in between the cells of the gastrointestinal lining start to widen. This widening allows the harmful microbial toxins and undigested food particles to enter the bloodstream, triggering the immune system to react and “fight off” these unwanted substances. This creates a cascade of inflammatory reactions and can cause inflammation to become systemic throughout the body.

Prolonged dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability, can heighten the risk of developing chronic disease conditions. These conditions can include a range from digestive disorders like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), to even autoimmune and metabolic disease.

“The incidence rate of chronic inflammatory disorders is on the rise in the pediatric population.

Crucial role in the interactions between an altered intestinal microbiome and the immune system in the development of several chronic inflammatory disorders in children — such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), autoimmune diseases, diabetes, and celiac disease.”

~ Frontiers In Immunology

“Continued dysbiosis has been associated with multiple chronic diseases such as obesity, cardiometabolic diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, autoimmune diseases, dementia, and others.”

~ Frontiers In Microbiology

“Unhealthy gut microbes generate metabolites that drive the progression of several cardiovascular pathologies like atherosclerosis, hypertension, heart failure, and type 2 diabetes.

The gut microbiome functions like an endocrine organ generating bioactive metabolites that directly or indirectly affect host physiology,”

~ W.H.W. Tang, M.D.

Cleveland Clinic. Nat Rev Cardiology.

“Gut Microbiome: Next Frontier of Precision Medicine.”

“The loss of protective bacteria means the immune system can’t regulate inflammation. Inflammatory chemicals escape from gut tissue to other parts of the body.

If the microbial community continues to be disrupted, these inflammatory cells can attack joints and set the stage for inflammation to affect internal organs.”

~ Dr. Jose Scher, MD.

Director Microbiome Center for Rheumatology and Autoimmunity,

NYU Langone Health